From Mirpur with Love by Ansar Ali, Grand Trunk Project Initiatve

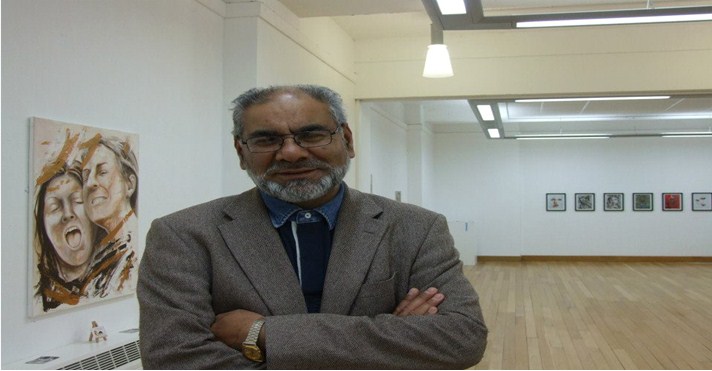

Ansar Ali, 60, came to the UK in 1969 from the rural Mirpur, Azad Kashmir and settled in Peterborough. As we explore the history of migration of Mirpuris to the UK, we asked Mr Ali to recount his family’s memories of Partition.

After Partition in 1947, Mirpur became one of the three districts of Azad Kashmir, azad meaning ‘free’. Yet, in administrative terms, Azad Kashmir remains autonomous only nominally. Roger Ballard (1991), a prominent scholar of British Asian community in Britain, writes:

“[A]lthough Pakistanis in both official and unofficial spheres have long tended to regard Azad Kashmir as having only the most peripheral significance in the national scheme of things, this region and its population has, in fact, made a considerable contribution to the economic wellbeing of the country as a whole.”

Mirpur has a special connection with UK’s Pakistani community, with some heavy investments made in the area by the British Pakistanis and a vast inflow of remittances in foreign exchanges. In the 1960s, and the *entire town was flooded in Mirpur to make way for a hydro-electric ‘Mangla’ dam build on the river Jhelum, designed and supervised by an English company, Binnie & Partners of London.

The construction of the dam “caused a large-scale exodus of Kashmiris”, with more than 100,000 people being evicted with most made homeless when the whole of the historical town of Mirpur and over 485 nearby villages were submerged.

The British government needed workers at that time, hence the decision was made to grant Mirpur evictees permits to work in the U.K., majority of which were placed in factories in the Midlands and the north of England. Many of these Kashmiri young male workers later invited their families over and now form one of the largest Kashmiri communities outside of Kashmir.

Mirpur and Partition

Before 1947, Mirpur was a predominantly Hindu-majority area. The Kashmir Valley area was predominantly Muslim with a substantial Brahmin minority, unlike Jammu where Hindus were in majority.

As Mr Ali told the GT Project:

“Apart from the fact that the majority was Hindu, and that consuming beef or slaughtering cows was difficult for them [the Muslim minority], people lived quite harmoniously together, side by side. My mum and dad remember that they had friends they grew up with [who were Hindu]. They have fond memories of growing up.”

“A lot of the people in these villages were not politically motivated. Their existence was from their land, support from one another in the village communities, regardless of what background they came from. When someone died, people would give their condolences and share the grief, irrespective of whether they were Hindu, Sikh or Muslim. People really did not make so much emphasis on difference that were political or religious.”

When asked about his parents’ memories of Partition, Mr Ali recounts that as the Partition process had begun people started moving about, and there were some horrific stories of murder and rape and the minority-Muslim community had to flee their homes not able to return for weeks because of safety reasons.

“It really was unimaginable. Sometimes we see in movies what happened, but they [my parents] witnessed all of this. Many people did not want to leave. This had been their home. Similarly, on the other side that is part of India now. The eldest son of my mum’s cousin was trapped and all his family is still there, in divided [Indian] Kashmir. We have never seen him nor his family. Unfortunately, he has died a few years back and we know nothing of his children.”

“In terms of Partition stories’, finishes Mr Ali, “I think people are reluctant to talk about them. Apart from my mother and father’s experience [as Muslims], no doubt there are Hindus and Sikhs who have their own stories to tell. I think it was a chapter in all of our lives, in history, that we should all learn from, and hope and pray that nothing ever like that happens again.”

For more information on the Grand Trunk Project visit: http://tgtp.co.uk/

British Pakistan Foundation Celebrates Historic Election Victory: 15 MPs of Pakistani Origin Elected to UK Parliament

The British Pakistan Foundation (BPF) is thrilled to announce

British Pakistan Foundation Denounces Racially Insensitive Language

The British Pakistan Foundation (BPF) condemns in the strongest